162: Campfire Series - ‘BLDGBLOG Turns 20’, with Geoff Manaugh

A conversation with Geoff Manaugh.

In this special Campfire Series episode, Geoff Manaugh joins the podcast to tell us the story of BLDGBLOG.

We discuss how he maintains an online presence while playing the algorithm games of social media and talk about the topic of content ownership and the evolution of blogging.

We also get into the creative opportunities Geoff has found by blending architecture with other disciplines, learn about his journey from blogger to author, talk about his Hollywood experiences with his fictional writing, and hear about some upcoming projects including a new book on archaeology.

Episode links:

- BLDGBLOG

- Geoff’s personal website

- Geoff on Instagram

- TRXL 008: ‘This Reminds Me of That’, with Geoff Manaugh

- Until Proven Safe: The History and Future of Quarantine by Nicola Twilley and Geoff Manaugh (Amazon)

- Ernest (Motherboard)

- We Have a Ghost (Netflix)

About Geoff Manaugh:

Geoff Manaugh is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer regularly covering topics related to architecture, design, and technology for publications such as The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, MIT Technology Review, WIRED, FT Magazine, and many others. He has taught graduate architectural design studios at Columbia University GSAPP, USC, and UC Berkeley, lectures at cultural venues around the world, and has exhibited twice at the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

In 2023, his short story, "Ernest," was adapted into the Netflix film, "We Have a Ghost," which was the #1 Netflix movie in the world for three consecutive weeks and reached #1 in 69 different countries. His 2016 book, "A Burglar's Guide to the City," was a New York Times bestseller for two consecutive months and was optioned for television by CBS Studios. His 2021 book, "Until Proven Safe: The History and Future of Quarantine," written with Nicola Twilley, was named a Guardian, Time Magazine, NPR, and Financial Times book of the year. Since 2004, he has also been the author of BLDGBLOG (bldgblog.com), read by millions in the two decades since it was launched.

Images from the episode

Click for a larger version. Find all these images on Geoff's Instagram.

Connect with Evan:

Watch this episode on YouTube:

Episode Transcript

162: Campfire Series - ‘BLDGBLOG Turns 20’, with Geoff Manaugh

Evan Troxel: [00:00:00] Welcome to the TRXL podcast. I am Evan Troxel, and today I welcome back Geoff Manaugh to this special Campfire series episode of the podcast.

Geoff is a Los Angeles based freelance writer covering topics related to cities, design, crime, infrastructure, technology, and more for the New York Times magazine, The Atlantic, Wired, The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Financial Times Magazine, New Scientist, Cabinet Magazine, The Daily Beast, Wired UK, and many other publications.

He is also the co author with journalist Nicola Twilley of Until Proven Safe, the History and Future of Quarantine, which was published during the pandemic in 2021, and in 2016 he published A Burglar's Guide to the City on the relationship between [00:01:00] crime and architecture. He also writes fictional stories that have been adapted into films, like his ghost story titled Ernest, and We Have a Ghost which can be found on Netflix. Now, if you heard that and are thinking, that doesn't sound like the normal type of guest for the show, you'd be wrong because Geoff has already been on the podcast. In this episode, we go off the beaten path and reflect on 20 years of BLDGBLOG, which is Geoff's blog and the evolution of online writing.

Geoff launched his blog on July 7th, 2004, and I invited him back after last speaking with him four years ago in episode number eight to talk about this rare internet milestone.

He recently put up an Instagram post that prompted me to reach out to him and catch up, and in that post he snarkily said, "Wild to think, it's been 20 years, I genuinely miss the camaraderie and friendship of the earlier phase of the internet, replaced today by an online culture so cynical and empty and sloganeering and [00:02:00] pointlessly embittered on every level. Alas."

And while that's true, Geoff and I continue to endeavor in creating valuable material for our audiences. And I've been a huge fan of his work for a very long time.

I also thought it was appropriate, as we find ourselves completely buried in AI generated content, found online today. And so, as we delve into today's conversation, Geoff provides valuable insights into maintaining an online presence while playing, or perhaps more appropriately, abstaining from participating in, the algorithm games of social media, the topic of content ownership, and the shift from traditional blogging to modern platforms like Substack. We get into the creative opportunities of blending architecture with other disciplines explored by Geoff, learn about his journey from blogger to author, his Hollywood experiences with his fictional writing, and upcoming projects, including a new book on archaeology.

As always, [00:03:00] my ask of you is to help the show by subscribing to TRXL on YouTube and in your favorite podcast app to let me know that you're a fan.

And if you're watching this on YouTube, Please click that like button that's right down below. And if you'd like to get an email when episodes are published with all the links and other information from the episode, sign up at TRXL. co. You can also directly support the show by becoming a member at the site as well. Thank you so much for listening and watching.

Okay, so now without further ado, grab a beverage, pull up a chair, and gather around the campfire as we celebrate two BLDGBLOG in my wide ranging conversation with Geoff Manaugh.

Geoff, welcome back.

It's been four years, almost to the day since you were on the podcast. You were a very early guest so this is a little bit of a [00:04:00] reunion, but it's an even bigger reunion of your blog turning 20 years old, which funny. I, okay. So I'm thinking about blogs in terms of timelines, and this is kind of geologic time for a blog and

you're super into geology and, and architecture and all these things too.

So maybe that's fitting. What do you think?

Geoff Manaugh: Well, yeah, I mean, it's a, it's, it's funny to think of my online writing as, as, uh, geologically aged. But, um, but yeah, in, in today's climate, that seems accurate. Yeah, 20 years is an extremely long time for, for a blog, especially because, I mean, blogs as such now are You know, have been replaced by newsletters and Tik Tok and even just longer posts on social media like Twitter and Or Blue Sky even for that matter But um, so yeah It's funny to look back and realize that it was 20 years ago this month that I first put anything up on on On the website and the fact that you and I spoke nearly four years ago is also pretty pretty pretty amazing

Evan Troxel: about that time, but not in one place. Like, I, I've, I've always been, [00:05:00] like, searching for, you know, so there was Posterous, and there was Tumblr, and there was the Mac blog, and there was Blogger, and I've been on all those. And, and then I eventually kind of settled into, you know. Um, where I was recently at Squarespace for a long time, and now I'm on Ghost, but, but, I, like, moving this stuff around is not easy, for one. How have you found the whole, like, you know, because, because ultimately you have a catalog of posts, you have books worth of posts. of posts, right? And it's like to have like the cotkey. orgs out there where it is a 20 plus year compendium of, of writing and stuff where it actually is all in one place. maybe there was some foresight there. I don't know. Did, did you plan ahead for longevity with this or what were you thinking?

Geoff Manaugh: I mean, I don't necessarily know how much I was thinking about genuine longevity, but I did think that the organizational, uh, pleasure of having all of my writing in one spot, and that [00:06:00] you would know where to find it, and that, um, you know, it was a, it was a single URL that you could visit, and I would just have, you know, basically an online portfolio of writing, um, that I could direct people to, um, was definitely a conscious decision.

Um, you know, there are, there were aspects of, you know, articles that I've written that, uh, to this day, even though, uh, I'm, I'm way less, uh, prolific on BLDGBLOG than I used to be. Um, but where I still kind of want to take old articles and just put them on BLDGBLOG, just simply to literally have them all in one spot.

Um, you know, to republish them there. But, um, but it's, I think it's great actually to have, have one's writing in, in one place. You know, there are a lot of people who I know who, similar to the description that you just gave of your own trajectory, you know, they've got writing all over the internet at different websites.

And Um, you know, some are defunct, you know, sort of, uh, groups that don't exist anymore or longer posts that they don't necessarily link to on older, on sites like Archonnect or, or that kind of thing. But, um, but yeah, having everything in one spot is, is great. Uh, the, the migration, I did actually change it at one point.

Um, I started, well, uh, BLDGBLOG on Blogger. [00:07:00] Uh, which, uh, you know, was pretty, uh, at the time was, was great because it was free and I didn't feel any obligation whatsoever to post because it wasn't, you know, it wasn't, I, I had no money in, uh, tied up in the, in the venture. Um, but around 2015, I think it was, I switched to WordPress and, uh, the migration, my friend Jim Webb, who's a, a, a web guy in, in, uh, Washington DC, was a, was a huge help with that. But migrating, you know, I think there were. I've deleted a lot of posts, but I think that there were something like 1, 600 posts that I had to migrate over from the old BLDGBLOG to get to the new, the new one on WordPress, and then, um, you know, it was There were some issues there too, just because every once in a while I'll reuse a title.

Like for example, I used to have a series of posts called Books Received, and it was just about books that I'm reading, or books that have been sent to me for reviews.

But I found, only after going back through my website on WordPress, that WordPress, the migration tool that we used, had mixed up the Books Received, so that like, a Books Received written in 2009 had been replaced by one written in [00:08:00] 2014,

and then I had to go back and figure out which ones were which, and you know, it was a It wasn't, wasn't very fun, but uh, but that's a minor, minor issue, you know, when the, when the, when the reward is that you have a place that you can post and you can get your voice out there and participate in, in the, in the larger architecture culture.

So, you know, the headaches, the headaches are worth it.

Evan Troxel: It's interesting to think of now with new context around ownership of your own stuff, right? So, I mean, to your point a minute ago, right? Blogging on other platforms like Medium or even on LinkedIn now, people put up longer articles. Um, there's, and they're not ours, right? Even, even Substack to a certain extent. It's your Substack, but it's still on Substack, right? It's a, it's a, and there's a reason people go to those platforms if they want to monetize their writing and have it behind a paywall or have subscriptions or whatever. But, for you to have your own place that you can monetize, It's yours, right? I think is, is kind of a, an interesting, [00:09:00] uh, it's, it's a great thing to have.

Like I, I own mine too. But the idea of having it all under your control is. I think something of value.

but it's also not where the eyeballs are anymore, right? even RSS is basically dead, right? When it comes to, to reading, we used to use Google reader to subscribe to RSS blogs or some other app that was an RSS reader.

So we would get notified at least when a new article was posted and we didn't have to visit a site that like, to your point, you're. You're not as prolific as you used to be on BLDGBLOG, right? So

BLDGBLOG, you maybe post every six months or something now, but it could have been any different timeframe.

It could have been three days. It could have been every day. It could have been multiple things a day, right?

Bloggers have different frequencies that they, that they publish stuff. And, and it was nice to just get notified and not have to go check.

And that's not even, nobody goes to anybody's website anymore.

Now you kind of have to have just a hookup to social media so that when you post people get notified and that's where they see it. [00:10:00] And they might. You might go back to your site to read it, whereas LinkedIn or whatever, people are doom scrolling on LinkedIn,

even, even on LinkedIn, right?

And they might see your,

your article there, uh, and, and, and, and catch when that you've published something, but it's a, it's a completely different world now.

And even with AI now, and just kind of, there's the recent thing that I've seen people trying to do is opt out of getting crawled by for AI training stuff. Um, and. I mean, this is something that architects are constantly worried about as well, with copyright and, and ownership of instruments of service and, and renderings and all this kind of stuff and, and being used for training data potentially.

And there's like, it's kind of a scary world out there right now. How, how do you feel about all that kind of stuff? Because Google used to crawl our stuff too, and it still does. Like I don't have a robots do text file that says, don't crawl this. Um. Because I do want to show up in search results, right? Um, and I publish my transcripts for my podcasts on my website and, and all that kind of thing [00:11:00] because I want to show up and, and also, you know, the exposure is nice, but also that, that it provides value when people do search for things.

How do, how do you feel about that whole side of things and platforms and monetization and paywalls and subscriptions? I mean, it's open ended, so you can take it wherever you want.

Geoff Manaugh: Yeah, no, I mean, it's a huge question, but, um, I mean, because the, I agree with you that the industry, uh, has changed, and I don't mean the architecture industry, but the, the, the field of online writing and of all kind of online content production, um, has changed dramatically in the last 20 years, and, uh, I do think that a lot of, I mean, if you look at, for example, what Elon Musk did with X, aka Twitter, Um, you know, the whole point for people who will pay for the premium subscription is that you'll just put, you know, a, a 4, 000 word post up on Twitter because you, you have enough space for it now.

And that's where the eyeballs are, that's where the retweets are, that's where people are who are actually going to read the content. And then also it algorithmically down, uh, ranks, um, links out to [00:12:00] things like BLDGBLOG or even to LinkedIn or certainly to Substack. You know, there was a

Evan Troxel: They all want native, native posted content,

Geoff Manaugh: Yeah, and then Google will do things like, you know, list your website and allow you to show up in search results, but often at the penalty, in my opinion, of having your material stolen for AI to study and that kind of thing. So it really is a different world that is controlled more top down. And, um, it definitely felt way more bottom up, so to speak, back when I started, which was that, yeah, you can just start almost like a media empire using a keyboard.

And, um, owning the copyright of your material, or at the very least, you know, doing sort of copy left, uh, sort of, uh, share alike, sort of, uh, licenses that, that, that were more popular at the time. Um, but, yeah, I mean, there's not, and I think this is one of the things that has affected my, I mean, many things have affected my pace of posting on, on BLDGBLOG, including other professional, uh, uh, obligations now.

Um, but one of them certainly was that, that, you know, uh, it's just harder, people don't, are, [00:13:00] are, are in, are, are substantially less likely, not just to go to a BLDGBLOG as a, as a kind of, um, you know, that people have just lost interest, but people just don't go to blogs as, as, as much as they do anymore.

So, I mean, the temptation would be, well, I could join, you know, I could start paying for an X account and start putting stuff there, or I could start, um, putting things on other platforms so that more people see them. Um, uh, but. It's, it's tough, I mean I feel like the payoff there is that certainly I don't want to, you know, writing for Twitter or X means that I'm just enriching other people who are profiting off of my material in a way that my own website shouldn't necessarily be something that they make money off of.

Um, but at the same time if it allows me to make money, like is it, is it, am I doing my own self a disservice by, you know, putting, not taking money that's sitting there on the table waiting for me to grab it? Um, by, by not, you know, being more flexible in the platforms that I use. But, um, you know, there are a lot of problems with WordPress and, and the, and the individual hosted blog anyway, but I think a lot of those are more like [00:14:00] technical and typographic and user based.

You know, there are aspects of, of WordPress in particular that I really don't like. There were, there were aspects of Blogger that drove me insane, which is why I left it. Um, there are aspects of Substack, having sort of experimented a little bit with Substack, that, that I also don't like. Um, I, I personally, the entire newsletter idea.

I mean, I know it's where everybody is right now, but I, the one thing in the world I don't want more of is email and, uh, the idea that, you know, I've, I subscribe to multiple Substacks and some of them are daily, but it's just like, my God, I wake up in the morning and I've got, you know, 12 emails and nine of them are Substacks and it's, it's pretty overwhelming actually, like I, I'm, I guess I'm old school enough that I, I would rather actually just go to your website and just see what you have there, you know, I haven't been there in two weeks or I haven't been there in a couple of days, like what's new.

Um, I know a lot of people find that too labor intensive, but I think it's worth it personally, and it's better than being having my inbox explode with just what feel almost like, um, [00:15:00] you know, those, those notes that used to exist in the 80s, what were they called, like, uh, you'd get a chain letter, you know, and then you were meant to forward it on to somebody else, but, uh, it just, it just sort of feels a little overwhelming to constantly get everything as an email.

Evan Troxel: Well, and those nine Substack emails are book length, right? Like, they're

Geoff Manaugh: Yeah, totally.

Evan Troxel: book length, but they're, they're cliff

Geoff Manaugh: They're, they're articles. yeah, yeah,

Evan Troxel: and, and it's a lot of reading, and I mean, and this is coming from somebody who publishes really long podcast episodes, right? So, uh, it's just, it's just a different medium.

It's, it's kind of, it's similar in, in, you know, total output. It's a lot to listen to. And it's interesting to me to think about podcasting as kind of actually being one of the only places where it was like the true intention of the web, which was like, it was Yes, it was the Wild West, but it was, it was open and it was yours,

right?

To create that media empire that you, you mentioned, right?

And that's what podcasting still is. I don't think Spotify is doing anything to [00:16:00] try to help that. I think they're trying to actually hurt that with. Right, creating, again, this is a platform, they're creating a platform and they're trying to get you to go to their platform and subscribe to their music and then you get the podcasting and all those kinds of, and, and that is against kind of the, the original idea, just like so many businesses are against the original intention of what the, the web was about or what podcasting was about.

So

it's kind of interesting to me that, Apple being the largest podcast directory in the world hasn't messed that up, right?

They

haven't intentionally screwed it up and tried to monetize it. Um, they've just kind of been a benevolent overlord of it in some way. Um, so, it is interesting to me to kind of think about how this is also another long form way to deliver. ideas, content, conversation to people like writing is on, on was on the blogs and on internet. And at least there's a [00:17:00] subscription model still with podcasting that works pretty well. And by subscription model, I don't mean pay for, I just mean like to subscribe to be notified

when, when episodes come out.

So, um, Yeah. it's, it's, it's a similar but different and I hope it doesn't change because companies are interested in changing it for sure.

Geoff Manaugh: yeah, it's interesting actually just listening to you describe that because, uh, I mean, I do think that so many of these, these super platforms are going out of their way to make sure that you never leave. So, you know, if you go to x. com, you know, you'll read this article and then this video and then you'll watch an entire feature length film that's been released on X or documentary or that kind of thing, and so you just never leave, um, or same with other social media platforms or even things like Apple, et cetera, et cetera.

Um, but what's interesting is that I think that, you know, the, you could arguably sort of compare that to the growth of things like big box stores that took something like a very specialist butcher, put that out of business by absorbing butchery into the meat department of, say, a Walmart. Um, and then there was, you know, a local clothing store that, [00:18:00] you know, was selling quirky t shirts, but now it's out of business because now Target is selling those quirky t shirts.

But this, this kind of thing where you get absorbed into a kind of retail empire. Um, you know, and even to the point now where, uh, there was a, a, a, a minor, I'm not gonna say controversy, but a minor conversation online about a plan for Costco to that was, uh, they were putting out, uh, a new building where in order to, uh, uh, go along with local regulations, had to add housing and residential, uh, uh, uh, space to the, to the Costco.

Evan Troxel: that.

Geoff Manaugh: Um, so the idea though, you know, just to be cynical for a brief moment, although I'm very pro housing and pro dense, you know, walkable, uh, urban cores, um, you know, cynically though, you know, it's like if you actually live at a Costco or the kinds of apartments now that you can buy that are actually in shopping districts, uh, basically inside shopping malls, um, it's kind of an extension of this idea that you can never leave the one place that you go into.

You're, you're now in the kind of retail super family and I, I definitely think that that's what X is trying to do under, under Elon.

Um, you know, where just basically, yeah, [00:19:00] like you'll have podcasts, you'll have feature films, you'll have, uh, you know, photography, uh, exhibitions, like you'll have live events, everything will be on this one platform.

Um, but I do miss the, that other earlier internet, you know, where you did go to the individual butcher and then this one strange bakery and then this one whatever. Um, because I feel like that's what it felt like in terms of going to just find individual people's voices and this is their website, this is how they designed their website.

Um, these are the things that they linked out to. It was, it was much more sort of personality based. And, um, I definitely miss that aspect of things where everything feels much more shoehorned into a kind of, even like with Medium, you know, you go to Medium and you can, you know, everything's in the same font, everything looks the same.

Um, you know, or Google's, um, their automated, automated page, uh, design, uh, thing that they, that they, that they put together, um, about 10 years ago now. But where it just basically made everything look identical, so,

the New York Times looked exactly like a post on BLDGBLOG, which looked exactly like, uh, somebody else's rant about something, which looked exactly like [00:20:00] a, a restaurant writing about, uh, you know, a, a new night that they had coming up.

And so the internet became much more difficult to differentiate between types of content, Um, types of voices and even levels of expertise where it was difficult to understand what you're getting in, into. Is this a, is this an essay or is this an op ed or is this an advertisement? Everything looked the same, even typographically.

And so I think that that also, in tandem with decreasing media literacy skills in the general public, I think has definitely led to a lot of the things that we see now, where people just do not know what to trust or who to trust or what to believe. And, um, I, I don't see a way out of that problem right now.

I mean, aside from perhaps it completely absurd minor changes, like allowing more, um, visual differentiation between, um, users of major platforms, like X or Medium, uh, etc, etc. There, you know, there has to be a way to make things that they don't all look like it's just internet mush, and you have to read through it and decide what's true.

Because I feel like that's the [00:21:00] situation that we're in now.

Evan Troxel: Yeah, it's a, it's a, the lowest common denominator kind of template, visual template. advertising of everything that, Facebook did it, I think, because

remember, MySpace was totally customizable, and then it

Geoff Manaugh: Yeah, notoriously.

Evan Troxel: were, and it was just the standard layout. You couldn't, you couldn't inject your own CSS code into the, into the boxes and, and make, make the flashing headlines anymore, because, I mean, at some level, like, yeah, it would, it looked really bad on MySpace, but at the same time, it was kind of yours, and so, Apple's done the same thing with the phone, right?

And it was, they, they don't let you do a lot of things because it wouldn't look like a great Apple device if everybody was allowed to do whatever they wanted to it. And so there's like this weird, it's your, it's your device, but it's not, you don't get to decide what it looks like,

right? As, as, as it's, you can see this kind of all over the place.

You can also see it in automobiles, right? Everything's starting to look like a Camry, for example,

right? It's like all the cars start to kind [00:22:00] of look the same.

And. But there's always kind of that culture that of outliers, but it's a very small percentage of people who actually do any of those things. So it could be car customizing.

It could be, you know, computers that could, you know,

there's, there are going to be people who still buy and build their own computers and run Linux. Right. So,

um,

Geoff Manaugh: It's a very small minority of people, but

Evan Troxel: it's a very small minority.

Geoff Manaugh: But you know, it's funny, it brings to mind, um, you know, the famous example of, uh, you know, the Gesamtkunstwerk in architecture, you know, where, uh, you know, if Mies van der Rohe is, is not only designing the buildings, but then also insisting on the placement of window shades, and the colors that those window shades can have, so as not to violate the artistic purity of the architectural space, of the structure.

Um, you know, I think arguably we're just kind of butting up against the kind of social media Gesamtkunstwerk where, you know, everything is being controlled, uh, for us. And, uh, and I don't like the results, so it's kind of funny, I wonder, um, you know, I don't want to sound like an old man yelling at a cloud, but I do [00:23:00] wonder what would happen if I moved into a building where I couldn't change the window, uh, you know, shade, color, due to the vision of the original architect.

Evan Troxel: Yeah.

Geoff Manaugh: It's interesting, but I feel like we're in that phase right now of the internet, or a comparable phase, I should say.

Evan Troxel: Right.

Right. yeah.

I mean, well, let's shift the conversation to what you do instead of writing on the internet, which is, well, you tell us, I mean, you're writing books, but you have other obligations as well. You're doing, you're doing a lot of stuff. Um, but There still is this option to write books, right?

Physical books, right? And to design the cover of those books and the layout of the books and the topography and the hierarchy visually and obviously the structure of the chapters and all this stuff so that it really is this stand alone thing. bespoke thing, right? Um, I mean, yeah, they end up getting mass produced, but, but this, it is a design, right? Um, so talk about your, your author, like where, where you been? Because the last time we talked, you had, you [00:24:00] were on the cusp of releasing a book about the pandemic that you started writing, I think in 2016, if I'm remembering correctly.

And so it was pre pandemic writing, you did a, and then the pandemic started and then you were. I think you said that the, it was at the publisher and it was like, okay, now we have to make some changes because a lot of this has, has happened now. And we know more than we did before you, before you started that publishing process. So take us kind of where we've been in the last four years since you were on the cusp of publishing your book on the pandemic

or pandemics, not the pandemic.

Yeah,

Geoff Manaugh: yeah, sure. I mean, specifically, um, yeah, the book is, um, it's about pandemics in the larger sense. Uh, it's specifically about quarantine as a spatial phenomenon and how architecture can be used to prevent the spreading of, of, uh, pathogens and diseases between people and animals and plants. Um, which I think is a, which I just, I just be, I'm specifying there because it's a, I'm trying to show that, you know, you can write about architecture.

Um, in ways that aren't necessarily, you [00:25:00] know, uh, stylistic criticism of existing buildings or historical monographs of architects who lived in, in the past. Uh, and I know there are a lot of other types of, of architecture writing. Um, but you can also look at how architecture plays roles in other fields.

And so, you know, um, my, the book before that that I wrote, A Burglar's Guide to the City, was about architecture in crime and crime prevention. Um, and specifically in the field of burglary, you know, which is a spatial crime because it involves, uh, illegally accessing interior space of architecture.

Um, and so with the quarantine book is similarly, it was looking at architecture as a, as a kind of frontline, um, medium through which we protect ourselves from the unknown.

Um, but so yeah, the book came out in, uh, 2021, came out ironically actually about exactly a year after our last, that, that conversation that we had, uh, because it came out in July of 2021. Yeah. And, um, since then, I, well, let me back up slightly. So since around the time of Berger's Guide to the City [00:26:00] came out in 2016, um, a kind of smaller secondary career of mine took off that then became my number one career, um, which was working in Hollywood for film and TV adaptations of things that I'd written.

And so, uh, that was gradually kind of growing in the background of all of these things and, uh, led to a situation where quite a lot of articles and short stories and even a burglar's guide to the city, uh, things that I'd written were getting optioned for adaptation in, in, in, in Hollywood. Um, and it got to the point where I think at one point I had 12 active projects.

Uh, you know, Hollywood is, is a funny place, so they'll, they'll often option something and not, literally not do anything with it. Or, or they'll take it all the way up to the finish line and then decide, Oh, nevermind. We're not going to, we're not going to work on this project anymore. Um, you know, which is sadly is what happened with the Burglars Guide to the City TV show.

Um, it got all the way up to the, the, the final decision about what they were going to release in the fall. And, uh, we had the pilot script, uh, anyway, everything was in place and then, and then, and then it [00:27:00] got turned down,

but, um, but yes. And then in 2023. Uh, a film finally did come out, a Netflix movie, uh, based on a short, short story of mine.

And, um, and that was exciting. It was really fun. I got to go to the, the red carpet premiere. And it was a, it was a Netflix movie, so it was only in the cinema for literally just one night, uh, when they showed it at their own cinema that's here, uh, a specially built place here in Los Angeles.

And, um, got to meet the, the stars and, and, uh, I knew, I knew the director already and that kind of thing.

But, um, so that was pretty, that was exciting, um, and for me. And, uh, but so yeah, in the last four years I've been working still on. Um, a lot of short fiction that is now in the adaptation pipeline. Um, I'm working on a new book now, um, and I'm still doing some reported non fiction for outlets like, uh, MIT Tech Review, Wired, I just had a piece in, um, Financial Times, uh, things like that.

Looking at different, different aspects of architecture. Cause still, at the same time that I'm, I'm diversifying maybe the audience for what I'm writing, um, I am still writing [00:28:00] about architecture. Um, in that sense that even a quarantine book is about architecture, uh, a book about a, a series of heists is about architecture.

Um, you know, even the story that got adapted into a Netflix film, um, was about a haunted house. Uh, so, you know, it's a, that's, that's a, uh, fundamentally has a, has a, an architectural, um, setting or an architectural structure around the, around the, the, uh, the idea of the story. And so, I think that that's, uh, going back to the conversation we were having about audience and platform.

Um, I definitely think that anybody listening to this should consider not just, um, you know, it's great to have your writing in one place online, um, but consider writing in different formats, uh, you know, writing in short fiction, maybe experiment with a screenplay, um, you know, do reported non fiction rather than just an essayistic or, uh, you know, just sort of a blog post.

Actually get in touch with people and do reporting. You know, quote people, go, go on first person reporting trips to see things in person and, and write about them. Um, and those kinds of things I think really do open doors in other [00:29:00] fields, whether it's a documentary film or whether or not it's a, you know, a feature film like the Netflix movie that I was a part of.

Um, but it's, there's a huge audience for writing and there's a huge audience for ideas and there's a huge audience for cultural production. Um, but I think it's easy to get frustrated when you put something up on a personal blog and it doesn't immediately catch fire. Um, well some of that is because people haven't seen it.

You know, it's the wrong audience. You might have an audience, uh, but it's not the right people for giving it, uh, getting it into the correct context to get picked up by Hollywood or that kind of thing. Um, but I think that if you're willing to seek out those kinds of audiences and try to figure out ways to write for them or get in touch with people or put your work in front of different audiences, um, I think the results can be really, really rewarding and fun.

And, um, for me, certainly have broadened the horizon of, of, of, uh, things that I cover and, and, and, yeah, where, where I cover them and that kind of thing, and, and for whom I do so. But, um, it's kind of a long winded answer to that question, but I feel like that's the kind of stuff that's been happening in the last four years, so, yeah, a lot of, [00:30:00] um, a new book, some Hollywood stuff, and, uh, some non fiction.

Evan Troxel: Interesting. And, and, like, you didn't plan that out in advance, right? It, it, like, it's it's interesting that, that what you're saying is you, you, you chased some of these, interesting ideas and they turned into something that opened a door for something else. And one of the things we talked about in our last episode was this idea of kind of connecting the dots.

You see these interesting connections. I mean, the name of the episode was this reminds me of that, right?

And, and so you, you, you're, you're just constantly observing and noticing and you see something and, oh, that reminds me of this thing over here. And that reminds me of this, The, the tunnels remind me of the subways and, and the inside of this and, and the under that.

And I think that that's really interesting how you're willing to chase those, not knowing where they're going to lead, which I think

is kind of like any design problem that's open ended. It's like a

wicked problem, right? You don't know where it's going

and you're figuring it out as you go down that path.

Geoff Manaugh: Yeah.

Evan Troxel: And to me, [00:31:00] like that, that's kind of what architects are, are built for, right? Like

that, that is, you're looking for interesting mashups, which I think every time I hear what you're working on, it's an interesting mashup. Like

I, Oh, I didn't think of those two things together before.

Right. And I think it's interesting that the kind of the thread that runs through this is architecture. And so we're, and we, we probably talked about this on the last episode, but it's been four years, so let's, let's refresh, like, where does that come from for you? Like, why, why is that the thread for you?

Geoff Manaugh: Uh, yeah, that's a, that's a good question. I mean, I can answer in the specific, I guess, uh, just, you know, for me in particular, I guess I, I, I, I noticed that so much of what I'm interested in, um, can be traced back to architectural or spatial questions. And so You know, as a child I was super interested in things like lost cities in the jungle and, uh, and, and ancient ruins [00:32:00] and I read a lot of, like, fantasy and played Dungeons and Dragons and I was really interested in the lost kingdoms of, uh, the past or whatever, but that's fundamentally it was about, it's an architectural obsession with,

um, lost buildings or abandonment or dereliction, um, and then similarly when I was got really into science fiction more as a teenager, um, you know, so much of science fiction is, um, Um, at the very least, set in an interesting environment, whether that's a, an alien planet, or a megastructure, or some kind of city, or a mining camp on an asteroid, or that kind of thing, but there's a spatial aspect to science fiction.

In fact, often in science fiction, the spatial setting, is the thing that makes it clear that it's science fiction. It's set on an alien planet. You know, it could be a, it could be a novel about a father and a son, but it's set on Mars. It's science fiction. Um, you know, or it's in a, it's set, you know, on a city on the Atlantic seabed.

Oh, it's science fiction. Um, the setting is often, um, not, it's not just the presence of technology or the fact that it's set in the future. It's [00:33:00] also the setting that it takes place in. Um, but so I also began to notice that with things like heist films, when I got really into, into those and crime. Um, that, uh, and, and, and, and those overlap quite quickly with things like action movies.

Um, but you, I began to notice that it's architectural, you know, that you have people in a heist movie are actually talking to one another explicitly and out loud about how you get from this room to that room. How do we get inside a building without no one

Evan Troxel: some wireframe 3D model that

Geoff Manaugh: Totally, exactly. Yeah, I mean, it's, it's one of the only genres that you can get away with people looking at blueprints.

And it's not boring, it's actually like key to the plot. You want to see those blueprints. Um, you know, it's really difficult to get away with that sort of architectural obsession. Yeah. Uh, in a different genre. I mean, other than maybe, uh, like a murder mystery where you're trying to figure out how somebody got into that room.

Um, but so, and then of course, you throw in actual architecture, by which I just mean buildings and the built environment and cities and trans questions of transportation and, uh, you know, uh, park design and streets and, uh, even [00:34:00] now things like sea level rise, um, and then the aesthetic aspects of that as well.

Buildings I like, quote unquote, you know, just something as simple as that. Um, you know, the things that I like to see, uh, or the buildings that I like to be in spatially and atmospherically. Um, you know, again, those are all spatial questions. Um, and then things like, uh, you know, other aspects of things that I'm interested in, like warfare, and, uh, the results of war, such as, uh, you know, refugees, and, um, the, the, the humanitarian aftermath of, of conflict.

Those are also architectural questions. You know, where do, where do people go, uh, What was the, the, the, what aspect, how was the destruction wreaked by the people who did it? Um, you know, there are a lot of, there are a lot of aspects of, of, of those kinds of, of questions that are, that are spatial and architectural.

But so, I say all that to, that, that I then realized that I could write a site like BLDGBLOG, and it was kind of a magic moment where I suddenly, where, uh, and it, and it switched on over about maybe the first year of writing the [00:35:00] blog, the first six months even, where It just became clear exactly how much someone can cover if they're still focused on architecture.

Um, and so I think that the last 20 years really were just exploring that. And so everything from astrophysics to, again, like, uh, um, geology and mining, uh, to, of course, the issues that we were just talking about, social issues of transportation, um, you know, aspects of historical preservation and archaeology.

Um, all of these things can be written about through an architectural lens. It's just right there in the middle of, uh, at least for me, of so many different interests. Um, you know, and for me that was a great realization that I can actually cover thousands of topics and it's still on the same website because it's all relevant to the same underlying topic.

Um, and so that for me was pretty, pretty, pretty magical. I mean, I could imagine someone doing that for, and people have done this, but, You know, for music, you could just look at acoustics and sound and not just music, but, um, you know, uh, just all kinds of different aspects of, [00:36:00] of, of vibratory energy that re that results in, in sonic, uh, material.

Um, you could do that with arts and art history. You could do it with a cinema. I mean, there's any number of different topics that you could take and just figure out ways of, of looping these other apparently irrelevant topics onto that. It's almost like an embroidery pattern. And, um, You know, but as far as, just to go back to your question, um, go, go chasing after something where I don't know where it will go, um, I do agree that that's something that a lot of architects do as well, because, I mean, when you sit down to design a building, or think about a house, or think about whatever it is that you're working on spatially, um, you clearly don't know exactly where things are, how you're going to get from, you know, Terminal 1 to Terminal 2, or from the first floor to the second floor, um, all of those things are questions that you solve as you work on the problem, and I find that as a, for me as a writer, and I think other writers do this differently, Um, I really enjoy not knowing where I'm going when I sit down and I start writing about something and, um, you know, this reminds [00:37:00] me of that.

The thing, the that that I just mentioned is often not even front of mind when I started writing about it. It's just that two or three paragraphs in, I'll remember something or realize, oh yeah, this. And, you know, the older I get, the more I feel like, um, writing for me is, is kind of the way that you see people, uh, you know, they play Sudoku or they, they do other cognitive games in order to try to keep themselves young or keep themselves fresh.

Um, but for me, that's writing. Um, you know, writing is my way of keeping cognitive connections open of, of discovering new ones, you know, of kind of keeping the brain flexible. And, um, I think that can happen in architectural design certainly, but, um, I definitely think that that's one of the reasons why writing for me is such an exciting practice.

Um, it's just a way to consolidate memories and build connections between things and try to remain cognitively. uh, attuned to the world in a way that, you know, knock on wood, you know, I can, I can stave off dementia for a few more decades, but, uh, you know, it's a, it's a, it's a good way to keep the brain flexible, and so I think that, yeah, that's a very long winded [00:38:00] answer to that question, but that's, those are some of the things that were so appealing, uh, about BLDGBLOG when I started it, uh, and, and remain appealing about architecture and writing, uh, today in terms of how one can organize one's own interests into something that can be communicated to others.

Evan Troxel: You and I are very alike when it, as far, I would, I would call you a man of merit, of many interests. You have a lot of different interests and I'm like that as well. And I encourage that on My other podcast, ArcaSpeak, to architecture students or people working in architecture is like, get away from the desk, get away from the computer, take those vacation days, go do things that you normally, like, don't, don't do staycations, right, go travel, see things, because it makes you a more interesting person, number one, to have experiences like those, but also those experiences lead back into your projects.

Right? Those are things that feed, and you never know when that's going to happen, you never know how it's going to happen,

you [00:39:00] don't even know why it's going to happen, but it's going to happen.

And that, I think, is what is so, what makes architecture interesting, because every project is pretty much a team sport, and everybody's bringing that to the team, and you don't know what that is.

Because every project is an assemblage of a different team, typically, right?

So, unless it's a small office, um, especially in big offices, teams disperse and they come back together in a different form on every single project, maybe even on different phases of a project. And, it's really interesting to me to see, I mean, it happened in school, it doesn't really happen in the real world, where, you know, there's one brief in the design studio, and you get 16 different Versions of that one brief, right?

Because everybody's bringing something different to the table. And I think that's what makes architecture really interesting. When you're solving a, it's a particular problem that can be solved a million different ways.

Right. And we're going to solve it the way that we solve it [00:40:00] because it is an organic thing.

But I think that's what's so interesting is what people are bringing to it. And so you, you have a list of interests, right?

And they, you've talked about a few of them, like geology, archaeology, uh, burglary, crime,

architecture. Uh, you're, you're a photographic enthusiast, right? You, you're, you do a bunch of different things.

You travel, you, you hike, you get outside. Um, Can you just talk about kind of what are those various things in a, in a better explanation than what I just gave of like the bullet list. But because the things that you, I, the main place I follow you now is on Instagram, and

this is where I see kind of where you're getting out and you are experiencing things.

And I can only assume that, I mean, obviously you love to do that, but it is also informing what you do as a professional.

Geoff Manaugh: Yeah. Yeah, I mean, it's a, I, I, you know, it's a, it's a, it's a, it's a big question, but I do think that travel is certainly a, a huge part of my, the way I sort of keep my batteries charged. Uh, [00:41:00] it's a big aspect of my life. Um. I don't know if, I mean some of it is maybe that, you know, I moved around a lot as a kid, so I got very used to showing up in new places, you know, we were, I was going to new schools every four, four years or so, um, you know, and I know that other people have moved much more than that, um, but nevertheless every four years, uh, since I was born, you know, I had to show up in a totally different state, go to a totally different school, and meet totally different people, and figure out a totally different lifestyle, um, you know, different regions of the country, different sizes of metropolises from a tiny rural town to cities.

Um, and so I think I've always enjoyed that, showing up in places and meeting people and seeing new things. Um, and, yeah, I was a very enthusiastic budget traveler when I first graduated from college. Uh, almost immediately, I'd say about two weeks after graduating. Um, you know, I was off to go backpacking, I was in China, I was in all over Europe, and that set a pace that hasn't necessarily flagged.

Um, it's easy because my wife and I don't have children or pets, so it's quite easy for us to leave the house [00:42:00] and go do things together. And, um, and not worry about things like, yeah, where the kids are going to be or what happened, what's going to happen to the dog or the cat or that kind of thing.

Um, but I do think that, yeah, taking the time to see places is, is super important, especially if one is interested in architecture.

Um, you know, being able to see certain, going into structures and experiencing them. It's really not even a seeing at that point, you know, you're experiencing, you're hearing, you're literally feeling a space. You know, whether or not it's a draft or. the temperature inside, or if it's just the fact that the ceiling is a hundred feet above you and the acoustics have changed.

Um, you know, just recently I was in Norway for a part of a reporting for the book that I'm currently working on, which is about archaeology, and somebody gave me a tip to go see this really fascinating museum. Um, it's, uh, it's two brothers, the Vigeland brothers, and I think it was the Immanuel Vigeland's museum.

Um, the other Vigeland is the brother who designed, um, a sculpture park, um, that is this incredibly [00:43:00] weird, uh, park in Oslo. Yeah, it's super strange. It's kind of homoerotic, but also sort of, uh,

a celebration of family and human virility. It's very, very strange. Um, but in any case, the, uh, the chapel, uh, that I went to, and maybe you've been there actually, um, was his brother's, uh, work where it's very weird.

It's a, it's a church cathedral, or sorry, it's a chapel, um, or chapel like space. That's, uh, it's quite a long walk. I walked there. It was a nice day. So it was about an hour walk from my hotel. Um, but it's in the outskirts of, of Oslo, and um, it's, when, when, when I went inside, uh, what was interesting is that it was so crowded I had to wait in the lobby before they would let me in.

Um, but then eventually when I went inside, I, uh, everyone else had left by the time I was standing in there, so I was actually alone inside this place. Um, but so there's very little light. Um, so when you first walk in, you cannot see if there are other people in the room, you can barely even understand what's happening.

Um, but the human eye gradually gets used to the darkness quite easily. In fact, amongst creatures, we have extremely good night vision. Um, and then gradually you realize that you're in [00:44:00] this huge room that has maybe 40, 45 foot tall ceilings. Um, all of the walls are painted with these weird, almost paganistic, uh, sort of, um, writhing bodies.

It's all very fertile and very kind of Scandinavian folk horror. It's very, very, very weird. It's almost a Dantean, uh, Um, and, and as that comes out of the darkness, uh, also, and I remember when I accepted the fact that I was alone, I realized that I could start making strange sounds. And so you, I got to experience the space acoustically, you know, through little claps or, or click, clicking my tongue.

In fact, I made a recording, uh, just to, to hear it, cause the, the decay on the sounds was, was like seven to nine seconds long. It was very, very long.

And, um, I, I mentioned that as an example because, you know, you can look at pictures of a, of an, of an interesting chapel outside Oslo, and you can say, wow, that looks really cool.

Or you can go to it and you can stand inside of it and you can feel the air and you can listen to the sounds, uh, and, and really kind of, uh, and even just adjusting your eyesight within a space and seeing more detail emerge as your eyes get used to things, [00:45:00] um, is a pretty incredible spatial experience.

And to be able to do that with other types of buildings, you know, I, I, I had a bucket list trip, um, in, uh, I think it was 2019 where I got to go to Cappadocia, which is part of Turkey where, uh, for hundreds and hundreds of years, the Hittites had dug huge underground cities. Um, into very soft rock that after it's exposed to air hardens.

Um, and so you have these massive labyrinths of underground cities that you can explore. And, uh, my wife and I went and just were inside these places for just hours and hours at a time. And then when you go out into the greater landscape, you find hundreds, literally, of, uh, abandoned Christian chapels. Um, 99.

9 percent of which have been defaced since, since the, they were constructed. Um, but the frescoes are still in there. So you find a hot, you know, from one side, it looks like a hill. And from the other side, it's like a broken open geode,

um, you know, which is a hollow rock with crystals in it. Um, but it's a broken open hillside that has an old Christian chapel, you know, with fading frescoes.

And then you realize looking [00:46:00] out over the landscape that you're surrounded by dozens and maybe even hundreds of churches that are just hidden inside hills. Um, it's a, it's an amazing experience. And so, um, you know, and let alone going to major tourist sites, like going to the Colosseum in Rome or going to, uh.

Angkor Wat in Cambodia, or seeing the Great Wall of China, or, you know, other large architectural undertakings. But so, you know, travel isn't cheap. But on the other hand, you know, you can, when I, I know when I was fresh out of college, I was, it was quite easy to get student deals. I still have some of my old student ID, IDs that you could get international student identity cards and get really good discounts on things.

And, yeah, totally. And I mean, I definitely, I, I think that's a hugely valuable aspect of things. And then you mentioned hiking. I do think that Um, I know that not everyone is a, is a big hiker, and everyone has different levels of physical ability to, to, to do these sorts of things. Um, but to those who are physically able to hike, I do think that it's a, an incredibly invigorating and, and exciting way to experience the landscape, to actually be out there, um, [00:47:00] outdoors.

Uh, you know, if you go to places like Zion National Park in, in, in Utah, or Canyonlands, um, the architectural forms that are revealed, uh, some might use the word architectonic instead of architectural, which implies human design. Um, but the architectonic forms that are revealed over long term of, uh, erosion and uplift and earthquakes and landslides and just like general rainfall over millions of years.

Um, you end up with these absolutely beautiful sort of hulking geometric forms that you can walk around and you can experience the shadows and listen to the wildlife. And it's a really architectural experience. You know, it's a spatial way to engage with landscape. Uh, it's a way to bodily invest oneself in the world.

And, um, I think all of those experiences are, are, are very important. Um, having said that, you know, other things are also quite important. Like, I think as an architect, um, or rather for architects, I also just recommend looking outside of the architecture building. Um, not just by going to the Grand Canyon, but literally look at things that are happening in different [00:48:00] departments.

Uh, look in different fields if you're not in school anymore. Um, you know, you might find something quite fascinating if you go to an astronomy conference, or if you go watch a movie about something you didn't realize you were interested in. I often find with a lot of architects who are very pressed for time, as you know, architecture is a notoriously overworked field, um, that there's a feeling of, not urgency, but of lack of time, and so, you know, if you're going to go see a movie, I know, I know many architects who feel like, well then it might as, it should be as architecturally relevant as possible, or if I'm going to read a novel, it should be a novel that is as architecturally relevant as possible, because I don't have, I don't have a lot of time to read a murder mystery.

I don't have time to go see this kind of thing. Um, but I find very often, not always, but I, I, a very, very high track record of success and going to places outside of the field of architecture and finding something where you're like, Oh, wow. I hadn't thought of that from a spatial point of view, or the fact that what they're talking about has to be designed by somebody.

Um, you know, [00:49:00] I mean, even just an example is in the quarantine book, you know, we went to an agricultural, uh, disease research center that was under construction. And, you know, you might think to yourself, what does agricultural disease research have to do with architecture? Um, but we actually got into this conversation with this guy who's designed the building, um, about things that I had just never thought about, like, uh, extremely advanced HVAC systems that allow negative pressure disease research labs to maintain negative pressure, so the air is always pumping out of the room.

Or no, excuse me, I take, I take that back. The room is, it's the other way around. The, the, the air is always pumping into the room to keep the pathogen isolated. Um, but it was a building designed to get, uh, to survive being hit by a, a category five or a level five tornado. And so the idea is that when you have even extreme barometric changes in the atmosphere outside the internal barometric systems of the, of the building will, will maintain their own pressure and the way in which that was maintained and, and the technical expertise that that requires.

Um, you know, my point is that that is an [00:50:00] architectural phenomenon and it's a technical question. And you wouldn't know that if you didn't necessarily follow, you know, disease research or, for that matter, looking to tornado proof, uh, you know, cities and, and structures in the, in the Midwest. Um, but I just think looking outside the box generally makes you realize how little is inside the box.

And I think that that's a really important lesson, uh, in my opinion for life in general. You know, don't assume that your life inside the box is everything, because it's not.

Evan Troxel: Yeah. Yeah, you, you really strike me as kind of an explorer or adventurer for sure. And, and the idea, like some of the pictures that you've posted of your travels in Southern Utah through the national parks, like my wife and I got married in Zion. I mean,

that's one of the reasons we chose that space.

Right. And I've done slot canyons there and we, we hiked the narrows for our, our wedding party, right? Like that

was what we did instead of. you know, doing it a golf course, right? So, um, but, but because it is so architectural and the national [00:51:00] parks of, of Utah are absolutely incredible.

Geoff Manaugh: Mm.

Evan Troxel: It's just like, they are kind of edifices, right?

But they're, they're just natural. And like hiking out to Delicate Arch and Arches National Park, right? It's, it's, it's, you, you you go on a journey to experience this thing and you wait for sunset and you walk back under the full moon and it's, it's absolutely incredible to have those kinds of experiences.

And they do inform the work that we do. I mean, it's, you can't not have it inform the work that you do. And it, I think it, it makes for some really interesting ideas to come out of. Who knows where they come out of, right?

It's like you can't even explain it. But,

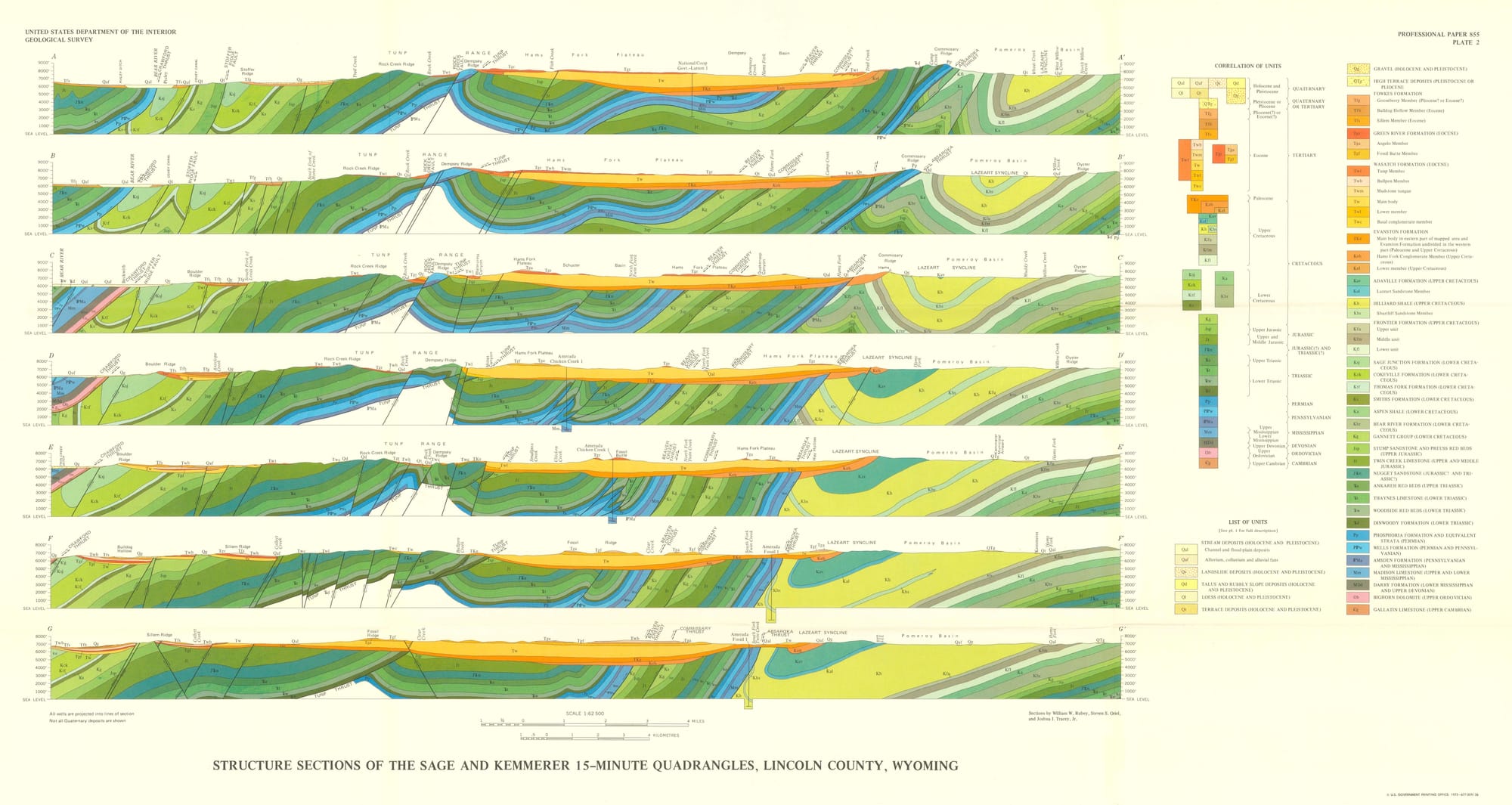

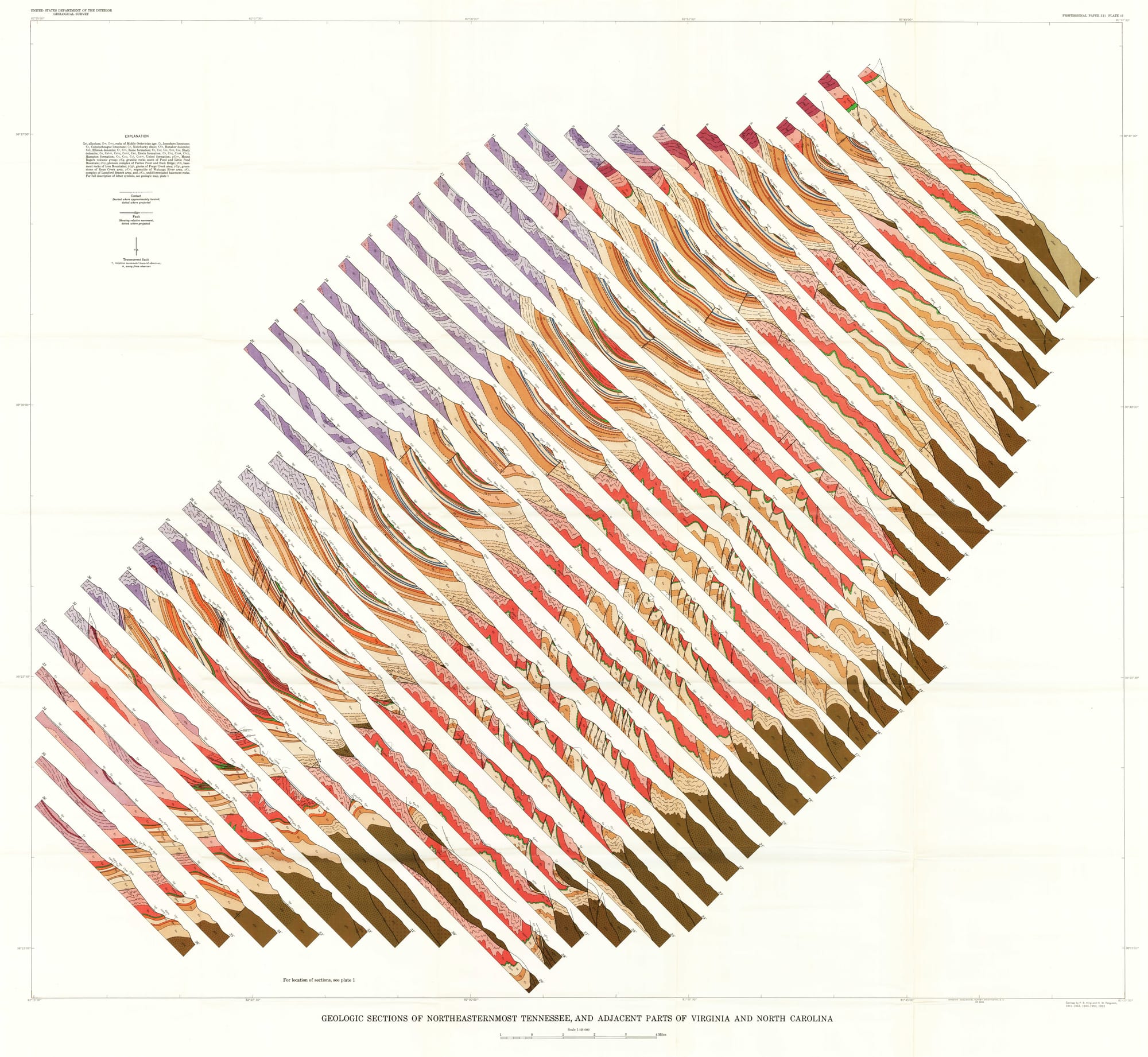

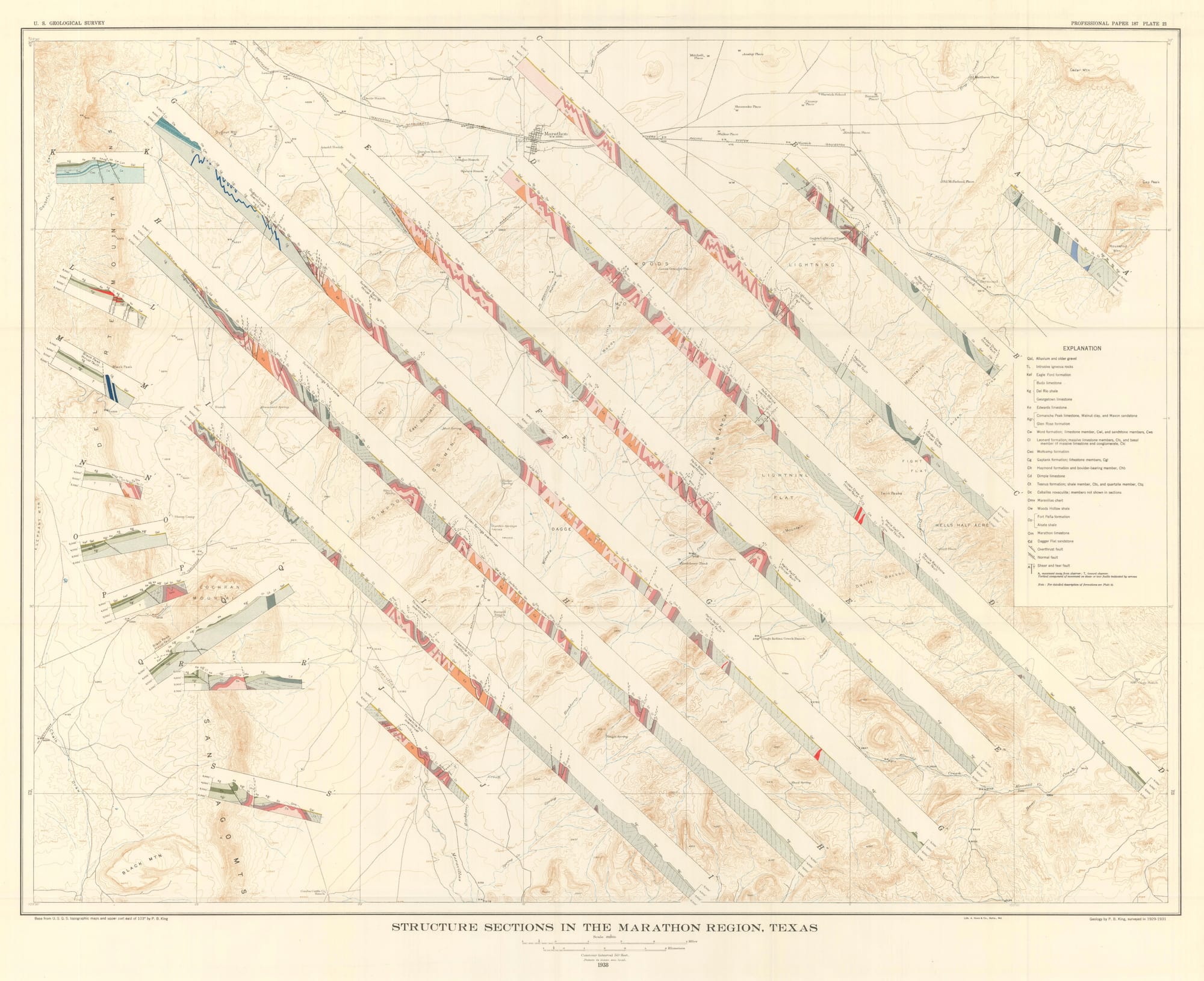

but there's some, there's some really interesting work that you've posted on your Instagram where you've, We've kind of done deep dives into geologic illustration, right?

And I remember following those really closely because you're kind of unearthing from these, that are out there, right? [00:52:00] People have done these really intricate cross sectional drawings through, through the earth and,

and you're relating it back to kind of a spatial nature. Like,

I think we talked about this in the last episode, right?

It's like, we don't, it's not just the ground that we stand on, right? It's like, there's a lot going on under the surface. Spatially with plate tectonics and with stratification and the bending of all that and just, it's kind of a, it's an ever evolving thing as well. It's not static, it's dynamic.

And I think to me, maybe you could just explain kind of what, what that study was that you did because I, I'll throw some images here into the, into the video portion of this for those who are interested in

seeing what I'm talking about.

But, uh, The, the, the things that you were surfacing, I thought they're, they're really beautiful, scientific, right? They were, they

were done for research, but they're amazing drawings. And, and

I think that's what's interesting about the work that you're doing, Geoff, because, I mean, you're a writer, but you're [00:53:00] also very visual in the presentation of the work that you're doing. And I can see kind of how, where you're drawing that inspiration from, because you're kind of doing this deep dive into case studies or, or again, just kind of chasing Um, a trail down and not knowing where it's going to go and you're finding some really incredible stuff.

Geoff Manaugh: Yeah, the geology stuff, um, was, uh, er, is, uh, yeah, just delightful to look at, and I think that some of that goes back to, uh, one of those sort of if this, then that sort of realizations, which was that, you know, if architects are looking at space through things, through visual techniques like section, and if geologists are doing something similar when they're going to see, say, a road, what's known as a road cut, so when, um, you know, someone built a road through a hillside, you then see what was inside the hillside, so you can see levels of rock, etc.,

the straight, the stratification of the rock, you know,

Evan Troxel: Can I just pause you for one second? Because we've talked about this, I think, offline. But, like, my grandfather was a geologist. [00:54:00] We mentioned it in the last podcast. But he did a study in Death Valley of a road cut, and it's a very famous road cut. It's actually published in, like, one of the top 10 road cuts, like the

total geology nerd stuff, right?

But it's, like, number two in the top 10 road cuts kind of compendium out there.

So it's just funny, like, when you bring that up. These are the kind of thoughts that are flooding my mind. Mm

Geoff Manaugh: that right there would be, uh, you know, the top ten road cuts. That would be a fun architectural project for someone to take it upon themselves to go visit those. You know, go see the top ten road cuts. Um, there's a, there's one I really like that's just north of the city here in Los Angeles.

Um, it's right when you're driving into a city over the mountains called Palmdale. Um, but as you drive through, it actually, the cut goes more or less through the San Andreas Fault. Um, you are a little bit off the fault, but, um, it's still a spectacular way to see the kind of, like, compressed waves of rock that have been jostled and, and deformed over millions of years by tectonic movement along the San Andreas.

Um, but I would definitely say that if that isn't in that, in that [00:55:00] list of top 10 road cuts, it should be. But, um, but yeah, so I think the realization that geologists are visualizing internal layers of the earth in a way that architects are doing for the internal layers of a building, um, was a really exciting thought process and led to Um, at one point I was teaching a class at Columbia GSAP that was looking at the San Andreas Fault as a setting, um, where the idea was to, for students to design a San Andreas Fault National Park, and, um, it was also there too where I challenged some of my students to, to develop representational techniques that could be applied to architecture and the earth, so that you could see, you know, what was beneath your feet, but also, uh, what was inside a building.

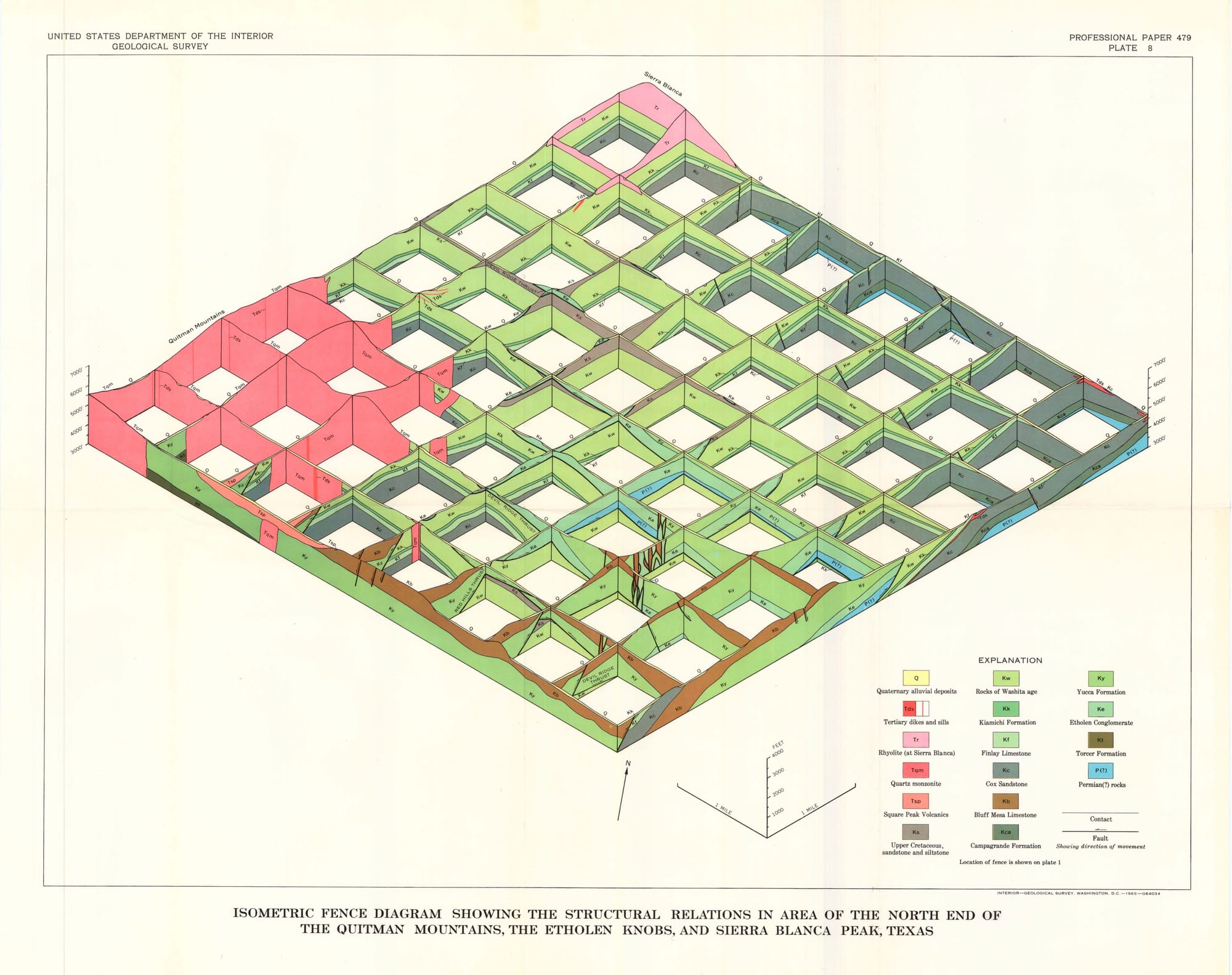

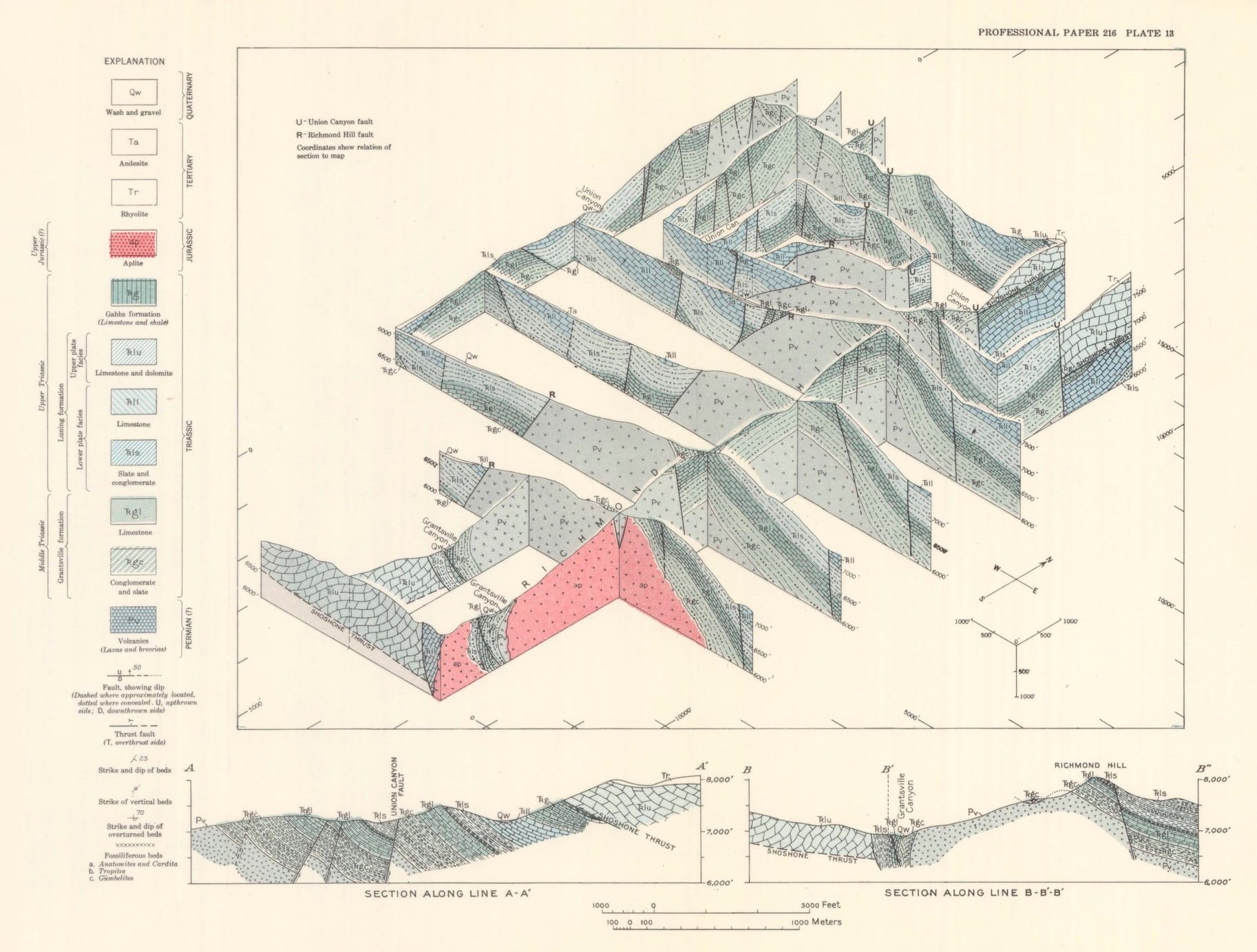

Um, and then, so, when I started looking into these USGS, the United States Geological Survey, um, the, these documents and reports that have been, that are all uploaded and free. It's one of the reasons why I'm a, you know, patriotic taxpayer, because I feel like, you know, we have incredible government services, um, and, and I'm a fan of those, but [00:56:00] so the USGS has this amazing archive of, of free geological research that's published, and, uh, the ways in which they, the, the geologists and the geological illustrators that they worked with, Figured out how to represent complex landscapes are incredible and I think that if you could show those or adapt those to an architectural setting Um, there are things like the, one of my favorite techniques is called a fence diagram Um, which is basically you're taking a section not just through one hill or one part of the landscape You're taking a section behind it and then a section behind it But then you're also taking sections perpendicular to those So you end up,

Evan Troxel: it's

a grid of sections,

Geoff Manaugh: Totally, yeah, exactly, exactly.

And so, you know, you could imagine a fence diagram, a grid of sections cut through Boston or, you know, or cut through London, you know, cut through wherever you might want, cut through Cappadocia, the place in Turkey I just mentioned. Um, you know, the things that would be revealed by that is, would be absolutely incredible.

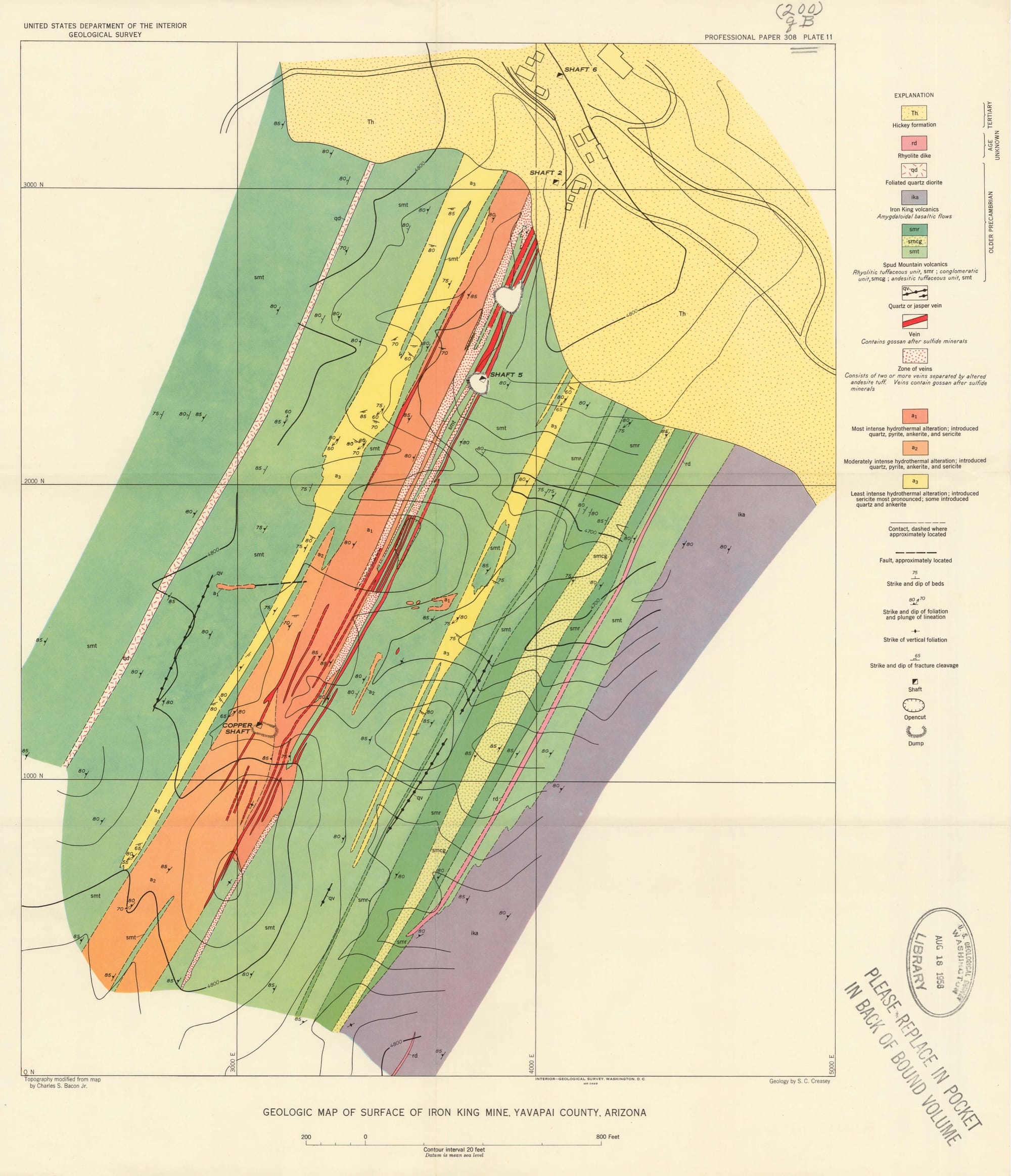

Um, and then also [00:57:00] isometric diagrams of mines, um, uh, maps of, uh, of mine tunnels, you know, that the USGS has produced, where You'll often have, you know, one layer of the tunnel in one color, or excuse me, one layer of the mine in one color, um, and then below that, uh, looking, you're looking at a plan, a sec, a plan of the mine.

Below that will be a different color, which will be mine level two, and below that is a different color. And you end up with these things that almost look like, you know, sort of, um, you know, abstract art meets a kind of mandala. And, you know, just the, the, and then as, as you know, from working in architecture, you know, um, mentally unpeeling what layer goes where and how they're connected, um, you know, goes back to the sort of the cognition stuff we were talking about earlier.

Like, it's a great way to just sort of keep cognitively flexible because you understand what you're looking at visually. And I mean, these tools then,

yeah, exactly, yeah, you're interpreting it.

Evan Troxel: like, it's like using AutoCAD, where different layers were just represented with different colors,

or different elements where, where, you know, you [00:58:00] had seven colors or eight colors that you would boil everything down to, but you knew exactly what you were looking at, just based on the color that the line was, right?

Geoff Manaugh: And, uh, I think that those kinds of things are beautiful to look at, scientifically communicative, and inspiring in terms of architectural thinking or architectural representation. And so, I still have unbelievable quantities of those geological, uh, materials, so I should, I should continue uploading them.

But, um, the, uh, the amount of stuff on the USGS website is, is unbelievable. And then, and then, and then, not only just those kind of 3D mappings, but even just, uh, or 3D diagrams, but, um, two dimensional maps that have been drawn that show the sort of weird fractal geometric forms that exist beneath our cities.

If you follow where the bedrock goes, or where the bedrock changes from one type of rock to another, or where it becomes topsoil, you get these shapes and lobes and outgrowths that look a lot like fractal [00:59:00] geometry, but are actually just what's beneath us all the time. And we just don't see it like that, because we can't peel away the soil, or for that matter, lift St.

Louis up in the air to see it, to look into the ground. But that's what's underneath St. Louis, you know, or that's what's underneath Oklahoma. Um, and also I find that many places that are allegedly quite uninteresting. You know, the, the fame, the famous boredom of the American Great Plains. Um, when you look at it in a geologic map, it's actually spectacular.

It's, you know, it's an unbelievably interesting place. And it goes to show that if you change how you represent something, you can often change your own level of interest in that thing. So to say that something is boring just means that it's been represented in a boring manner to you so far. Um, and there, there's a new way of looking at it and that, that those ways exist.

And so it's also exciting to see. Um, the USGS is a kind of a way of changing, um, yeah, changing how we think about representation and how we think about, uh, what, what we're capable of producing in terms of depicting, depicting the earth. But, um, but yeah, I mean, I think also then, you know, getting in [01:00:00] touch with geologists has, has been pretty exciting.

I've, I've, I've spoken with many geologists and, uh, plate tectonics researchers and all of this stuff informs my writing, my thinking. Um, and I certainly think it would be true for others as well, you know, to speak with people outside of your chosen field and get to know even just the vocabulary that those people use.

You know, like a fence diagram. It's an interesting, it's an interesting phrase to have in my pocket.

Evan Troxel: heard of that before

I saw that post that you had done.

Geoff Manaugh: yeah, and so,

Evan Troxel: I didn't know what that was called.

Geoff Manaugh: yeah, so getting, challenging your students to design fence diagrams of, uh, you know, buildings would be, would be quite exciting.

Evan Troxel: right.

Yeah,

you strike me as a very much of an inside out, like the way that you experience things, uh, you like, it's, it like you said earlier, it's spatial, I think a lot of architects are kind of outside in, we, we, We start at a very high level, we zoom in, zoom in, zoom in, zoom in, then we zoom back out, and then we zoom in, and then it's kind of this constant modulation between zooming out and zooming into the big picture and the tiniest details. And [01:01:00] obviously there's a spatial component to that and how all these things come together and spaces that people inhabit that are the things we actually create, but there's still kind of this aesthetic tendency that we, but you're talking about an experiential. Spatial, acoustical, right, light, like these are very architectural, like the very foundations of architecture, and I think it's so interesting to think about the spatial, they're not, They're not buildings, but they're still, a lot of times, they're man made things, like mines, like you were talking about, like subways, and different, uh, ways to convey people and objects through space, and mine shafts with, with carts, and obviously the shafts part, and it just seems to me like they're so experiential in nature.

I think that's really interesting, in the way that you, you even communicated, experiencing that chapel in Norway, right? It's, it's very inside. First, [01:02:00] outside, maybe second. I don't know. Um, but, but the idea of that experience I think is, is really the, the nugget of, of this part of the conversation because you don't get that looking at images.

Right? You just, you talked about that earlier. You, you, you can't just flip through Pinterest or Google or as it used to be magazines and books or in school we would do case studies. It was never the same as going to school. the place and experiencing it for yourself. And maybe even doing that multiple times. A recent, a recent example for me with this was, you know, I had seen images and I had heard other people talk about, um, the African American museum on the national mall, right in Washington, DC. And that's not the full name of it, but the full name of it is very long and I don't remember it exactly. So, uh, I'll, I'll put it in the show notes, but what an experiential. Museum to visit. I don't know if you've been there or not, but it's, it's, it's, you know, it's, I've been to the [01:03:00] Guggenheim in New York as well, and that is experiential, right? Like, it's like, go to the elevator, go to the top, and then work your way back down. And this one, it was the opposite. It's like, go to the bottom, and experience a timeline from beneath the ground, dark, and it still gets lighter and lighter, and, and it's, this progression through spaces on the inside is absolutely phenomenal.

Like, it blew me away. And it's not something you can take in in one sitting. Visit either, right? You need to go multiple times. There's so much content. There's so much to read. There's so much to think about. Um, I think that it, it is unfortunate that we are always so pressed for time working on projects and, and you don't get to take the time to really build your rapport with space as it were, right?

Doing these things to be able to then take that experience and apply it to your work that you do. Um, I mean, obviously people can choose to do that, but oftentimes it's like that these are the things that end up on the back [01:04:00] burner. But the work that you're doing, you're, it seems like you're very intentional about doing these travels, having these experiences. Um, if you were to, if you were to kind of lay that out for people, like how much time are you spending? I'm sure there's a blend, like you're probably working while you're doing this stuff too. But, but if

you were, the experience side versus the doing side, like what, what do you feel like you're, Your breakup is there, or the percentages of those.

Geoff Manaugh: I mean in terms of travel specifically, or

Evan Troxel: yeah, just, just like the experiencing of the, all of the different things that I see you posting about versus like the actual, like you're sitting down to write. And if you were

Geoff Manaugh: oh sure,

Evan Troxel: give some numbers to that.

Geoff Manaugh: um, uh, well yeah, I think that that number definitely changes over time. I think that, not that, and not in one direction, but there are phases in my life where quite a lot of time is spent more reflecting on things and writing about them. Whereas there are other times where it's very much more sort of doing centric, [01:05:00] so to speak.

Um, you know, where it's about the experience, it's about taking things in. Um, I find that when I'm traveling, one of the things that's so good about, and I like so much about being a writer is that it's quite difficult to not find something to write about. Uh, especially if you're traveling to a location where you're already kind of in Keyed up to see things because you're in a, you're in a different location.

You don't know, you don't know what's going on. So you're noticing more, um, very basic things that people take for granted as a, as part of everyday life, seem really exotic and strange. Um, you know, travel has that effect of heightening your sensitivity to detail. Um, and so if you also go, and that's even for people who aren't writers.

So if you, if you are a writer or a photographer or doing anything involving documentation. Um, you know, you'll begin to notice that, wow, I could actually write a piece about this building, or about this person, or about this place that I visited, or this landscape, or this historic site. Um, and so, it often means that when I'm traveling, I get to [01:06:00] see things that I might not otherwise have expected to see, or that I might not otherwise have gotten access to.

Um, because if you get in touch as a, as a journalist in town, you know, often it's, it's much easier to, for doors to be open to, to you. Um, and so that's one aspect of, of, of this that I like so much. So there's a, there's a, a friend and colleague of mine who, who I admire, um, who started an entire organization called the Infrastructure Observatory, um, because I can't remember this place he was trying to get into, but I, I want to say it might have been a data center.

Um, but the origin story was that he was trying to get a tour of a data center and they were like, why would we give you a tour of our data center? Who are you? Are you with an organization? And so about, he came away from that with the realization that, uh, all he, all he

had to do, yeah, so he started this thing called the Infrastructure Observatory, um, and then got back in touch with some of these people and, and, you know, got a group of four or five other infrastructure nerds together.